Pilex

By I. Gorok. University of Virginia.

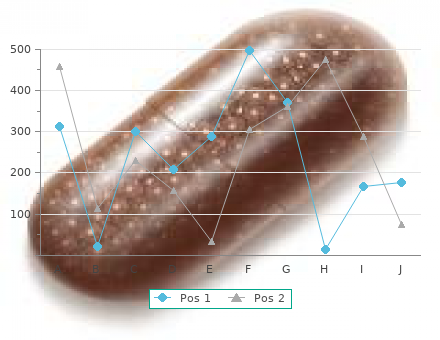

Once a newly transformed variable is obtained generic pilex 60 caps with visa, its distribution must be checked again using the Analyze → Descriptive Statistics → Explore commands shown in Box 2 60 caps pilex. Explore Case Processing Summary Cases Valid Missing Total N Per cent N Per cent N Per cent Log length of stay 131 92. Also, the skewness value is now closer to zero, indicating no significant skewness. The values for two standard deviations below and above the mean value, that is, 1. However, since case 32 was not transformed and was replaced with a system missing value, this case is now not listed as a lowest extreme value and the next extreme value, case 28 has been listed. In practice, peakness is not as important as skewness for deciding when to use parametric tests because deviations in kurtosis do not bias mean values. In the Tests of Normality table, the results of the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro– Wilk tests indicate that the distribution remains significantly different from a normal distribution at P = 0. Such gaps are a common feature of data distributions when the sample size is small but they need to be investigated when the sample size is large as in this case. Although log length of stay is not perfectly normally distributed, it will provide less biased P values than the original variable if parametric tests are used. Thus, the interpretation of the statistics should be undertaken using summary statistics of the transformed variable. If a variable has a skewed distribution, it is sometimes possible to transform the variable to normality using a mathematical algorithm so that the data points in the tail do not bias the summary statistics and P values, or the variable can be analysed using non-parametric tests. If the sample size is small, say less than 30, data points in the tail of a skewed distribu- tion can markedly increase or decrease the mean value so that it no longer represents the actual centre of the data. If the estimate of the centre of the data is inaccurate, then the mean values of two groups will look more alike or more different than the central values actually are and the P value to estimate their difference will be correspondingly reduced or increased. For this, statistics that describe the centre of the data and its spread are appropriate. Therefore, for variables that are normally distributed, the mean and the standard deviation are reported. In presenting descriptive statistics, no more than one decimal point greater than in the units of the original measurement should be used. The standard error of the mean provides an estimate of how precise the sample mean is as an estimate of the population mean. It is rare that this value would be below 30%, even in a child with severe lung disease. Therefore, the standard deviation is not an appropriate statistic to describe the spread of the data and parametric tests should not be used to compare the groups. If the lower estimate of the 95% range is too low, the mean will be an overestimate of the median value. If the lower estimate is too high, the mean value will be an underesti- mate of the median value. In this case, the median and inter-quartile range would provide more accurate estimates of the centre and spread of the data and non-parametric tests would be needed to compare the groups. Measuring changes in logarithmic data, with special reference to bronchial responsiveness. Two-sample t-tests are classically used when the outcome is a continuous variable and when the explanatory variable is binary. For example, this test would be used to assess whether mean height is significantly different between a group of males and a group of females. A two-sample t-test is used to assess whether two mean values are similar enough to have come from the same population or whether their difference is large enough for the two groups to have come from different populations. Rejecting the null hypothesis of a two-sample t-test indicates that the difference in the means of the two groups is large and is not due to either chance or sampling variation. To conduct a two-sample t-test, each participant must be on a separate row of the spreadsheet and each participant must be included in the spreadsheet only once. In addition, one of the variables must indicate the group to which the participant belongs. The fourth assumption that the outcome variable must be normally distributed in each group must also be met. If the outcome variable is not normally distributed in each group, a non-parametric test such a Mann–Whitney U test (described later in this chapter) or a transformation of the outcome variable will be needed. However, two-sample t-tests are fairly robust to some degree of non-normality if the sample size is large and if there are no influential outliers. The definition of a ‘large’ sample size varies, but there is common consensus that t-tests can be used when the sample size of each group contains at least 30–50 participants. If the sample size is less than 30 per group, or if outliers significantly influence one or both of the distributions, or if the distribution is clearly non-normal, then a two-sample t-test should not be used. In addition to testing for normality, it is also important to inspect whether the variance in each group is similar, that is, whether there is homogeneity of variances between groups. Variance (the square of the standard deviation) is a measure of spread and describes the total variability of a sample.

Phenylephrine discount pilex 60caps online, methoxamine (Vasoxyl) generic pilex 60caps with amex, and metaraminol (Aramine) (1) These drugs produce effects primarily by direct a1-receptor stimulation that results in va- soconstriction, increased total peripheral resistance, and increased systolic and diastolic pressure. Metaraminol also has indirect activity; it is taken up and released at sympathetic nerve endings, where it acts as a false neurotransmitter. Xylometazoline (Otrivin) and oxymetazoline (Afrin) (1) These drugs have selective action at a-receptors. Clonidine (Catapres), methyldopa (Aldomet), guanabenz (Wytensin), and guanfacine (Tenex) (1) These antihypertensive agents directly or indirectly activate prejunctional and, prob- ably, postjunctional a2-receptors in the vasomotor center of the medulla to reduce sym- pathetic tone. At higher, nontherapeutic doses, it activates peripheral a-receptors to cause vasoconstriction. Ephedrine and mephenteramine (1) These drugs act indirectly to release norepinephrine from nerve terminals and have some direct action on adrenoceptors. Amphetamine, dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine), methamphetamine (Desoxyn), phendime- trazine (Preludin), modafinil (Provigil), methylphenidate (Ritalin), and hydroxyamphet- amine (Paredrine) (see Chapter 5) (1) These drugs produce effects similar to those of ephedrine, with indirect and some direct activity. Phenylephrine, methoxamine, norepinephrine, and other direct-acting a-receptor sympa- thomimetic drugs are used for short-term hypotensive emergencies when there is inad- equate perfusion of the heart and brain such as during severe hemorrhage. Ephedrine and midodrine (Pro-Amatine), prodrug that are hydrolyzed to the a1-adrenoceptor agonist desglymidodrine, to treat chronic orthostatic hypotension. The use of sympathomimetic agents in most forms of shock is controversial and should be avoided. Fenoldopam (Corlopam) is a selective dopamine D1-receptor agonist used to treat severe hypertension. Epinephrine is commonly used in combination with local anesthetics (1:200,000) during infiltration block to reduce blood flow. Epinephrine is used during spinal anesthesia to maintain blood pressure, as is phenyleph- rine, and topically to reduce superficial bleeding. Phenylephrine and other short- and longer acting a-adrenoceptor agonists, including oxy- metazoline, xylometazoline, tetrahydrozoline (Tyzine), ephedrine, and pseudoephedrine, are used for symptomatic relief of hay fever and rhinitis of the common cold. Long-term use may result in ischemia and rebound hyperemia, with development of chronic rhinitis and congestion. Metaproterenol, terbutaline, albuterol, bitolterol, and other b2-adrenoceptor agonists are pre- ferred for treating asthma. Phenylephrine facilitates examination of the retina because of its mydriatic effect. Hydroxyamphetamine and phenylephrine are used for the diagnosis of Horner syndrome. Dexmedetomidine (Precedex), a novel selective a2-adrenoceptor agonist that acts centrally, is used intravenously as a sedative in patients hospitalized in intensive care settings. Other uses include ritodrine and terbutaline to suppress premature labor by relaxing the uterus, although the efficacy of these drugs is controversial. The adverse effects of sympathomimetic drugs are generally extensions of their pharmacologic activity. Overdose with epinephrine or norepinephrine or other pressor agents may result in severe hypertension, with possible cerebral hemorrhage, pulmonary edema, and car- diac arrhythmia. Increased car- diac workload may result in angina or myocardial infarction in patients with coronary insufficiency. Phenylephrine should not be used to treat closed-angle glaucoma before iridectomy as it may cause increased intraocular pressure. Sudden discontinuation of an a2-adrenoceptor agonist may cause withdrawal symptoms that include headache, tachycardia, and a rebound rise in blood pressure. Tricyclic antidepressants block catecholamine reuptake and may potentiate the effects of norepinephrine and epinephrine. Some halogenated anesthetic agents and digitalis may sensitize the heart to b-receptor stimulants, resulting in ventricular arrhythmias. The pharmacologic effects of a-adrenoceptor antagonists are predominantly cardiovascular and include lowered peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure. Phentolamine (Regitine) is an intravenously administered, short-acting competitive antago- nist at both a1- and a2-receptors. Prazosin (Minipress) (1) Prazosin is the prototype of competitive antagonists selective for a1-receptors. Others include terazosin (Hytrin), doxazosin (Cardura), tamsulosin (Flomax), and alfuzosin (Uroxatral). Prazosin has a slow onset (2–4 h) and a long duration of action (10 h) and is extensively metabolized by the liver (50% during first pass). Labetalol (Normodyne and Trandate) (1) Labetalol is a competitive antagonist (partial agonist) that is relatively selective for a1-receptors and also blocks b-receptors.

Ciprofloxacin can be used to treat an- thrax generic pilex 60caps on line, and erythromycin is the most effective drug for the treatment of Legionnaires disease discount 60 caps pilex fast delivery. Steven-Johnson syndrome is a form of erythema multiforme, rarely associated with sulfonamide use. Patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency are at risk of developing hemolytic anemia. The antibiotic classes that inhibit the 30S ribosome include amino- glycosides and tetracycline. Inhibitors of the 50S ribosome include chloramphenicol, erythromycin, and clindamycin. Bacterial cell wall inhibitors include penicillins, cephalosporins, and vancomycin. Often rifampin, ethambutol, streptomycin, isonia- zid, and pyrazinamide are used for months together, as many strains are multidrug resistant. Patients with increased risk of Neisseria meningitides infection can be given rifampin for prophylaxis. Amphotericin is used in the treatment of severe disseminated candidiasis, sometimes in conjunction with flucytosine. It is often toxic and causes fevers and chills on infu- sion, the ‘‘shake and bake. Cycloserine is an alternative drug used for mycobacterial infections and is both nephrotoxic and causes seizures. Mefloquine is the primary agent used for prophylaxis in chloroquine-resistant areas. Doxycycline is used with quinine for acute malarial attacks due to multiresistant strains. Metronidazole is used to treat protozoal infections due to Giardia, Entamoeba, and Trichomonas spp. Mebendazole is used to treat round worm infections, and thiabendazole is used to treat Strongyloides infection. Ivermectin is used to treat filariasis, whereas praziquantel is used to treat schistosomiasis. Niclosamide can be used to treat tapeworm infections, and pyrantel pamoate is used to treat many helminth infections. Valacyclovir is related to acyclovir, both of which are used for the treatment of oral and genital herpes in immunocompetent individuals. Vidarabine is used in more severe infections in neonates as well as in the treatment of zoster. Because cancer may potentially arise from a single malignant cell, the therapeutic goal of can- cer chemotherapy may require total tumor cell kill, which is the elimination of all neoplastic cells. Early treatment is critical because the greater the tumor burden, the more difficult it is to treat the disease. A therapeutic effect is usually achieved by killing actively growing cells, which are most sensitive to this class of agents. Because normal cells and cancer cells have similar sensitivity to chemotherapeutic agents, adverse effects are mostly seen in normally dividing nonneo- plastic cells, such as bone marrow stem cells, gastric and intestinal mucosa, and hair follicles. Achievement of the therapeutic effect may involve the use of drugs, sometimes sequentially, that act only at specific stages in the cell cycle (e. Primary resistance is seen in tumor cells that do not respond to initial therapy using cur- rently available drugs. The probability that any tu- mor population has primary resistance to two non–cross-resistant drugs is even less likely (approximately the product of the two individual probabilities). In this case, cells overproduce cell surface glycoproteins (P-glycoproteins) that actively transport bulky, natural product agents out of cells (Table 12-1). As a result, the cell fails to accumulate toxic concentrations of several different types of drugs. Resistance may occur due to the inability of chemotherapeutic agents to reach sufficient ‘‘kill’’ levels in certain tissues (e. Clinically useful alkylating agents have a nitrosourea, bis-(chloroethyl)amine, or ethylenimine moiety. The electrophilic center of these agents becomes covalently linked to the nucleophilic centers of target molecules. These agents also target other critical biologic moieties—including carboxyl, imidazole, amino, sulfhydryl, and phosphate groups—which become alkylated. These agents can act at all stages of the cell cycle, but cells are most susceptible to alkylation in late G1 to S phases. With the exception of cyclophosphamide, parenterally administered alkylating agents are direct vesicants and can damage tissue at the injection site. Some degree of leucopenia occurs at adequate therapeutic doses with all oral alkylating agents.

This shift in attitude has had rather paradoxical implications for the study of ancient medicine generic 60caps pilex free shipping. In short pilex 60 caps discount, one could say that attention has widened from texts to contexts, and from ‘intellectual history’ to the history of ‘dis- courses’ – beliefs, attitudes, perceptions, expectations, practices and rituals, their underlying sets of norms and values, and their social and cultural ramifications. At the same time, the need to perceive continuity between 4 For a more extended discussion of this development see the Introduction to Horstmanshoff and Stol (2004). Introduction 5 Greek medicine and our contemporary biomedical paradigm has given way to a more historicising approach that primarily seeks to understand med- ical ideas and practices as products of culture during a particular period in time and place. As a result, there has been a greater appreciation of the diversity of Greek medicine, even within what used to be perceived as ‘Hippocratic medicine’. For example, when it comes to the alleged ‘ratio- nality’ of Greek medicine and its attitude to the supernatural, there has first of all been a greater awareness of the fact that much more went on in Greece under the aegis of ‘healing’ than just the elite intellectualist writing of doctors such as Hippocrates, Diocles and Galen. Thus, as I argue in chapter 1 of this volume, the author of On the Sacred Disease, in his criticism of magic, focuses on a rather narrowly defined group rather than on religious healing as such, and his insistence on what he regards as a truly pious way of approaching the gods suggests that he does not intend to do away with any divine intervention; and the author of the Hippocratic work On Regimen even positively advocates prayer to specific gods in combination with dietetic measures for the prevention of disease. Questions have further been asked about the historical context and representativeness of the Hippocratic Oath and about the extent to which Hippocratic deontology was driven by considerations of status and reputa- tion rather than moral integrity. And the belief in the superiority of Greek medicine, its perceived greater relevance to modern medical science – not to mention its perceived greater efficacy – compared with other traditional healthcare systems such as Chinese or Indian medicine, has come under attack. As a result, at many history of medicine departments in universi- ties in Europe and the United States, it is considered naıve¨ and a relic of old-fashioned Hellenocentrism to start a course in the history of medicine with Hippocrates. This change of attitude could, perhaps with some exaggeration, be described in terms of a move from ‘appropriation’ to ‘alienation’. Greek, in particular Hippocratic medicine, is no longer the reassuring mirror in which we can recognise the principles of our own ideas and experiences of health and sickness and the body: it no longer provides the context with which we can identify ourselves. Nevertheless, this alienation has brought about a very interesting, healthy change in approach to Greek and Roman medicine, a change that has made the subject much more interesting and 5 For an example see the case study into experiences of health and disease by ‘ordinary people’ in second- and third-century ce Lydia and Phrygia by Chaniotis (1995). An almost exclusive focus on medical ideas and theories has given way to a consideration of the relation between medical ‘science’ and its environment – be it social, political, economic, or cultural and religious. Indeed ‘science’ itself is now understood as just one of a variety of human cultural expressions, and the distinction between ‘science’ and ‘pseudo-science’ has been abandoned as historically unfruitful. And medicine – or ‘healing’, or ‘attitudes and ac- tions with regard to health and sickness’, or whatever name one prefers in order to define the subject – is no longer regarded as the intellectual property of a small elite of Greek doctors and scientists. There is now a much wider definition of what ‘ancient medicine’ actually involves, partly inspired by the social and cultural history of medicine, the study of medical anthropology and the study of healthcare systems in a variety of cultures and societies. The focus of medical history is on the question of how a soci- ety and its individuals respond to pathological phenomena such as disease, pain, death, how it ‘constructs’ these phenomena and how it contextualises them, what it recognises as pathological in the first place, what it labels as a disease or aberration, as an epidemic disease, as mental illness, and so on. How do such responses translate in social, cultural and institutional terms: how is a ‘healthcare system’ organised? How do they communicate these to their colleagues and wider audiences, and what rhetorical and argumentative techniques do they use in order to persuade their colleagues and their customers of the preferability of their own approach as opposed to that of their rivals? How is authority established and maintained, and how are claims to competence justified? The answers to these questions tell us something about the wider system of moral, social and cultural values of a society, and as such they are of interest also to those whose motivation to engage in the subject is not primarily medical. As the comparative history of medicine and science has shown, societies react to these phenomena in different ways, and it is interesting and illuminating to compare similarities and differences in these reactions, since they often reflect deeper differences in social and cultural values. Introduction 7 and public hygiene and healthcare, and how they coped – physically as well as spiritually – with pain, illness and death. In this light, the emergence of Greek ‘rational’ medicine, as exemplified in the works of Hippocrates, Galen, Aristotle, Diocles, Herophilus, Erasistratus and others, was one among a variety of reactions and responses to disease. Of course, this is not to deny that the historical significance of this response has been tremendous, for it exercised great influence on Roman healthcare, on medieval and early modern medicine right through to the late nineteenth century, and it is arguably one of the most impressive contributions of classical antiquity to the development of Western medical and scientific thought and practice. But to understand how it arose, one has to relate it to the wider cultural environment of which it was part; and one has to consider to what extent it in turn influenced perceptions and reactions to disease in wider layers of society. The medical history of the ancient world comprises the role of disease and healing in the day-to-day life of ordinary people. It covers the relations between patients and doctors and their mutual expectations, the variety of health-suppliers in the ‘medical marketplace’, the social position of healers and their professional upbringing, and the ethical standards they were required to live up to. It is almost by definition an interdisciplinary field, involving linguists and literary scholars, ancient historians, archaeologists and envi- ronmental historians, philosophers and historians of science and ideas, but also historians of religion, medical anthropologists and social scientists. Thus, as we shall see in the next pages, medical ideas and medical texts have enjoyed a surge of interest from students in ancient philosophy and in the field of Greek and Latin linguistics. Likewise, the social and cultural history of ancient medicine, and the interface between medicine, magic 7 See, e. Indeed, my own inter- ests in ancient medicine were first raised when I was studying Aristotle’s Parva naturalia and came to realise that our understanding of his treat- ment of phenomena such as sleep, dreams, memory and respiration can be significantly enhanced when placing it against the background of medical literature of the fifth and fourth centuries. Fifteen years later the relevance of Greek medicine to the study of ancient philosophy is much more widely appreciated, not only by historians of science and medicine but also by students of philosophy in a more narrow sense. Scholarship has, of course, long realised that developments in ancient medical thought cannot be properly understood in isolation from their wider intellectual, especially philosophical context. And even though this awareness has occasionally led to some philosophical cherry-picking, it has done much to put authors such as Galen, Diocles, Soranus and Caelius Aurelianus on the agenda of students of ancient thought. Furthermore, the study of ancient medicine has benefited from a number of major developments within the study of ancient philosophy itself.

9 of 10 - Review by I. Gorok

Votes: 272 votes

Total customer reviews: 272